The Raleigh Cotton Mills Story.

Yarn. Storage. Distribution.Site Location

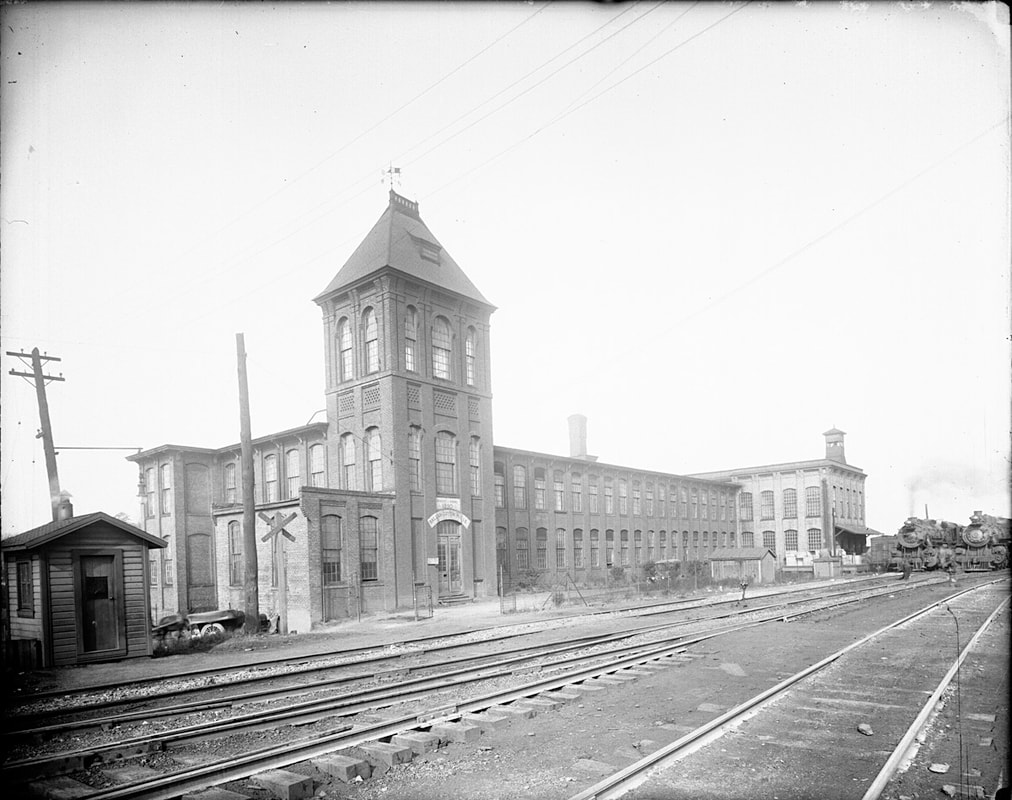

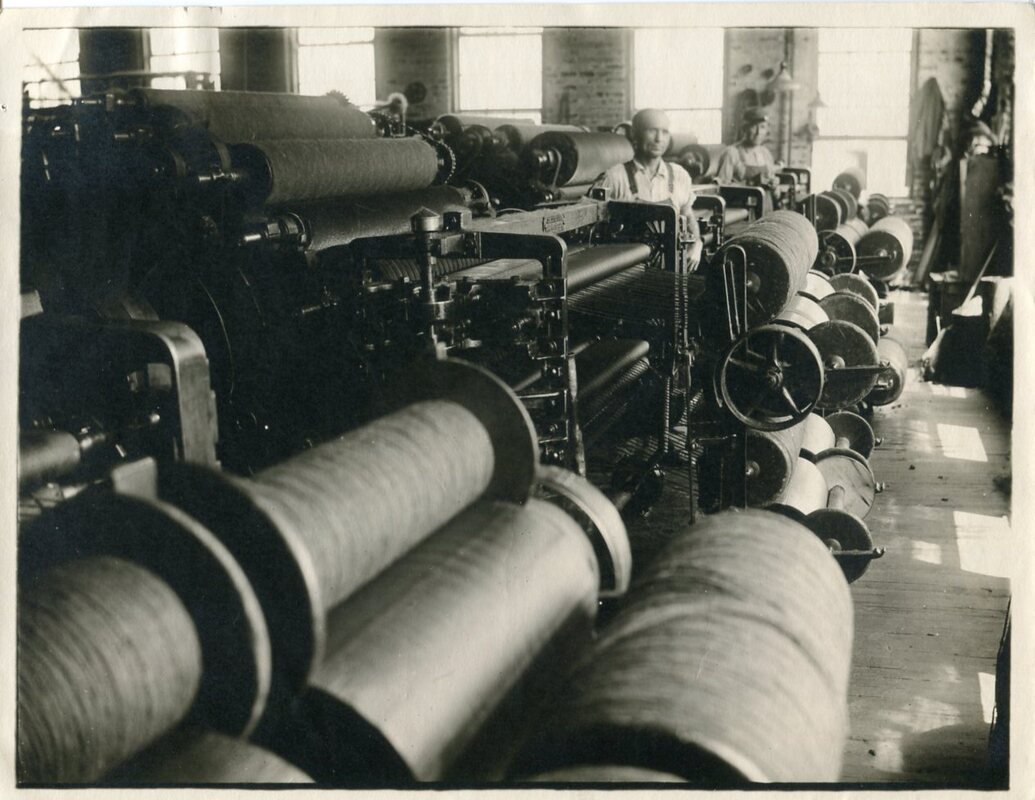

The Raleigh Cotton Mills building is a substantial landmark in Raleigh. It is located at a major entrance to downtown Raleigh near the busy intersection of Capital Boulevard and Peace Street. The building is prominently sited on a hill and is positioned on a north-south axis along the western edge of the Seaboard Air Line railroad track, so that its western facade faces towards Capital Boulevard. Historical Background The movement to build a cotton mill in Raleigh began as early as 1875 and accelerated throughout the 1880s. The movement was influenced by the great success of cotton mills in other southern cities. In 1875 the Daily Constitution wrote: "How about that cotton factory? Wilmington has one, Charlotte is thinking about establishing one and Raleigh should not be behind the times. Merchants and capitalists, awake from your lethargy, and see if something cannot be done toward adding this improvement to our enterprising city.7 Industry in the South had escalated in the post-war years, and the consolidation of the state's railroads into the Southern Railway System and the Seaboard Air Line was proceeding rapidly. " In this climate, the city's leaders were intent on establishing more industrialization in its region with Raleigh as the center of manufacturing and distribution. This was seen not only as possible, but as Raleigh's destiny. In 1888 Josephus Daniels, prominent editor of the State Chronicle, was instrumental in convening a meeting to discuss establishment of a cotton factory in Raleigh. Mayor Alfred A. Thompson and merchant W.C. Stronach were involved in this effort. The meeting bore results. Proponents for a cotton factory encouraged the city's residents to invest in cotton mills, promising that "...the real estate of the city would rapidly increase in value, and hundreds of employees would earn a living who now find it very difficult to find employment." Ten prominent citizens served on a committee to gather information on erecting and operating cotton mills; the newly formed Chamber of Commerce joined the effort; and a year and a half later in May of 1889, $62,000 had been raised through the Chamber's sale of stock in the future mill. By that summer the Chamber had selected directors for the Raleigh Cotton Mills Company and purchased six acres of land from Paul C. Cameron and his wife, Ann R. Cameron. The land selected was near Wolf Branch and fifty feet west of the main track of the Raleigh and Gaston Railway (later the Seaboard Air Line Railway). The 1889 deed included an easement to run pipes underground to convey water from Wolf Branch" .. as necessary for the purposes of a cotton factory." By March of 1890, construction was complete and the building waiting for machinery. The building sat empty for some time; pledges had not been paid, machinery could not be purchased. Despite these setbacks, the mill's chief backers remained fervent in their enthusiasm for Raleigh's "new industrial era. " In July of 1890 bonds were issued to finish the building and install the machinery, and operation began in August. Inside, the new mill had 6,000 spindles and operated eleven hours a day. In September, the Raleigh mill sent its first shipment to Philadelphia, and by October it was producing 1,500 pounds of spun yarn each day, with much of its production going to markets in the North. The mill's initial operations must have been a success, for two other cotton mills were built in Raleigh in the next years, the Caraleigh Cotton Mill in 1892 and the Pilot Mill the next year. With the increased efforts of the Chamber of Commerce, Raleigh continued to believe it was destined to be a large and important manufacturing center, and the Raleigh Cotton Mill's owners expected to build a mill village around the factory. By 1892 new railroad lines connected Raleigh to the North Carolina mountains and as far as Hamlet, making Raleigh an important railroad center. In that year, which was Raleigh's centennial year, sixty buildings were under construction. Around 1895, a large addition was built to the Cotton Mills. The Capital City was becoming a cotton mill town. Raleigh's timing was off. Cotton prices were dropping in the Panic of 1893, plummeting to four cents a pound in 1894. The area's new cotton growers quickly returned to other crops, and, as soon as it had started, Raleigh's success as the state's cotton-producing capital ended. The Raleigh Cotton Mills Company never recovered. Growth in the cotton industry slackened in the first decade of the 1900s as the price of cotton rose and labor became less plentiful than in the depression years of the 1890s. The market was hurt in part by agricultural problems that created higher prices for raw materials, and remained depressed for several years. In neighboring Durham, the Commonwealth Cotton Manufacturing Co. was out of business by 1913. The Morgan Cotton Mills, in the Commonwealth's old plant, survived until about 1930. The Durham Cotton Manuf. Co. also closed its doors around 1930. Sanborn Fire Insurance Company Maps show the Raleigh Cotton Mills building had become a fire risk by 1909, noting, "admittance and information refused." It remained a risk in 1914. In 1923 the Cotton Mills Company issued $100,000 of mortgage bonds, borrowing the money from the Virginia Trust Company of Richmond. The mortgage was agreed to by unanimous vote of the stockholders in January of 1923 "...for the purpose of the prosecution of the Company's business, payment of the Company's obligations and the purchase of new machinery... " The deed of trust was secured by the company's real estate including "mill and factory properties. This effort could not overcome the economic depression, and the company was unable to make the payments. It defaulted on its loan and lost the building at public auction in 1932. The property sold to C.B. Barbee and Henry T. Hicks, who assigned their bid to Wolf Branch Storage Company. Wolf Branch apparently used the building for storage until the mid 1940s. It was bought by Southern Jobbers, Inc., a wholesale warehouse. It appears from correspondence that Southern Jobbers was a subsidiary of Johnson Cotton Co. Both companies were headquartered in Dunn, North Carolina. The 1949 Sanborn Map shows Southern Jobbers, Inc., using both the southern and northern portions of the mill building for hardware storage and roofing materials, with an office in the southwest corner. A watchman was in the building. To the north in a series of long, one-story buildings was Southern Builders and Supplies, which stored building materials and apparently had a woodworking operation here. Another Sanborn map dated December 1950 identifies the building as the Raleigh Bonded Warehouse. Both sections of the building were sold, part in 1951, the other half in 1953, to Firwood Properties, a corporation named for the street south of the Cotton Mills. Firwood operated for Brown-Rogers-Dixson Company (BRD), which used the building successfully until 1995. The Brown-Rogers Company had been organized in Winston in 1880 as a retail hardware store. The company was started by Major T. J. Brown, J.M. Rogers, and W. B. Carter. These men had been engaged in the tobacco warehouse industry for years before creating their new venture; Major Brown was the first tobacco warehouseman in Winston. In 1915, W.N. Dixson, Sr., joined the company; its name changed when he became its president in 1924. In 1947, BRD branched out to Columbia, South Carolina, and a few years later bought the Cotton Mill to expand its operations to eastern North Carolina. BRD became one of the leading wholesale hardware distributors in North and South Carolina, as well as one of the region's major distributors of appliances. The company is run today by the third generation of the Dixson family. Changes in the use of the Cotton Mills building mirror the evolution of the textile industry through the twentieth century. The building's large spaces lend themselves readily to other uses. In 1995 the property was sold and was converted to 49 condominiums with a parking garage in the basement. ----- Construction Background // Fire Hazard Constructed in 1890 and 1895, over the years small additions and ancillary buildings were built on the property. Most of the smaller buildings have been demolished. The building is a good example of late nineteenth-century industrial architecture. Covered with a shallow-pitched gable roof, the long, two-story mill is characterized by rows of large, segmental-arched windows that occupy most of its four elevations. It is of solid brick construction in five-to-one common bond. A vernacular expression of the Italianate style is exhibited in the fenestration and decorative brick and millwork. Window bays are recessed to give the impression of pilasters defining the bays. The "pilasters" are further accentuated by corbelled brick brackets (at the eastern entrance projection) or wooden brackets to create a capital-like embellishment at the top which draws the eye up and adds verticality, counteracting the horizontality of the long building. A plain frieze and the sawn wooden brackets delineate the overhanging eaves of the roofline. At the time of its construction the mill was described as "a handsome two-story brick structure, ornamented at either corner with imposing towers and equipped with the most improved factory machinery." One tower was removed when the northern portion of the mill was added around 1895. 2 Windows of the later portion are wider than those in the 1890 section, but repeat the segmental arches and pilaster effect. The southeast corner tower is shown in a 1920s photograph as a three-story brick tower with pyramidal roof, topped by ornamental cresting and a weathervane. The tower's roof and ornamented top floor have been removed. Today, the tower has a flat roofline only slightly taller than the mill building itself. Immediately south of the tower is a one-story brick office added before 1909. The interior was typical of mills of the period, though larger than many. Its roof and floors are of a beam-and-plank construction system. The two main floors are large open spaces spanned by regular rows of decorative, round and fluted wooden columns supporting the heavy ceiling timbers at their joints. The Raleigh Cotton Mills is a well-designed building, intended to display a successful corporate image. The building's architect, contractors, and laborers remain unknown; however, the architect was familiar with up-to-date requirements of mill construction and used the tower, built as a fire safety necessity, as a focal point for ornamentation. Before the 1880s and 1890s, factory buildings generally were designed solely for function, with little attention to the aesthetic impression of their design. They were often of frame construction. At the Raleigh Cotton Mills, brick was used because it was a prestigious building material and added substance to the company's image. Brick was also selected because it was a fireproof building material. Fire prevention was an important consideration in mill design, and "slow-burn" construction became standard for mills. The basic design of most mills of this period was dictated by the requirements of fire insurance companies: thick outer brick walls, three- to four-inch-thick hardwood floors, and interior supports of massive wooden timbers. Facades were lined with large, multi-paned arched windows to provide light and ventilation necessary for the workers. The tower found at the Raleigh Cotton Mills and at most mills contained the water tank for an emergency sprinkler system. Insurance companies also encouraged the use of firewalls and tin-clad doors. The slowburn construction method reduced the seriousness of fires: buildings burned more slowly and enabled fire-fighters to get water to the building. The slow-burn construction did not reduce the number of fires, but reduced the degree of destruction. A review of available Sanborn Maps gives some information about the expansion of the Raleigh mill complex as well as a hint of its impending failure. The 1896 map tells us the mill made hosiery yarns, using coal-fueled steam for power and heat, and electricity for lights. The southern portion of the building, a long rectangular space, was used for spinning on the first floor and carding on the second. The later, northern portion is wider and almost square; it held cone machines on the first floor (basement), spinning on the second, and carding on the third floor. Other jobs were done in the central area with the one-story engine room (722 horsepower) and machine shop projecting to the west. This map notes a water tank on the top floor of the tower with a capacity of 14,000 gallons, and shows the location of hoses and water pipes. West of the building was a reservoir with capacity of 200,000 gallons, supplied by gravity, with a round settling basin just to the east. Shown north of the mill building is a small building for cotton waste and a cotton warehouse, both one-story. A spur of the Sea Board Air Line Railroad extended to a platform in front of the east elevation. To the southwest and facing Firwood Place were three shotgun houses. They were still there as late as 1949. The next available map is 1903. The capacity of the reservoir is shown as 165,000 gallons. It appears to be the same reservoir, so perhaps this was simply a corrected figure. By 1903 a small tower had been added to the center of the south elevation of the mill to hold a frame elevator. The two small ancillary buildings north of the mill had been replaced by three large, one-story cotton warehouses, a new, larger waste house, and a shed. The 1909 map shows changes to the building and also makes clear that the Cotton Mills Company was having difficulties. Between 1903 and 1909, the one-story brick office was built on the southeast corner of the building, south of the tower. In addition, the one-story platform shown on the 1896 and 1903 maps had been replaced with a two-story brick projection and a platform at the railroad track. Automatic sprinklers are shown throughout the building, which had a metal or slate roof and iron doors at interior openings. The three cotton warehouses were also sprinkled. However, we learn from this map that by 1909 the mill had become a risk: a notation reads, "FIA Risk, Admittance and Information refused. Survey from 1903 map." The map records fire safety information such as the presence of a night watchman with a clock and seven stations, and O'Donnell automatic sprinklers throughout. The supply for the sprinklers was from a 3,500-gallon tank in the tower 22 feet above the highest line of sprinklers. It was run by a Smith-Yale duplex steam pump at fifty gallons per minute taking water from a 64,000 gallon well supplied by gravity from the 165,000-gallon reservoir, and by city water pressure. The use of space was similar to 1896: the southern portion of the building held spinning on the first floor, carding on the second. the northern held winding and packing on the first, spinning on the second and carding, slashing and drawing on the third. In 1914 the mills were still labeled an FIA Risk. By this time the southern portion was designated as Mill No. 1 and the northern portion as Mill No.2. Exterior walls are shown as twelve to sixteen inches thick. The reservoir in 1914 had a Buffalo electric centrifugal pump driven at 750 gallons per minute. Two additional one-story cotton warehouses had been built, large coal bins had been added to the rail trestle, and two dwellings had joined the three shotguns on Firwood Place. Only the waste house is shown as "not sprinkled." The elevator at the south end of the building had been joined by another ..in the south end of Mill No. 2 (northern end). Uses had changed somewhat. Mill No.1 was used for storage in the basement, mule spinning on the first floor, and "carding, drawing, and speeders" on the second. Mill No.2 had mule spinning, winding and packing in the basement, mule spinning on the first as well, and, like Mill No.1, carding, drawing, and speeders on the 2nd. The central tower and hall shows "shooks" in the basement, pickers on the first, and lappers on the second. On this map, both portions are shown as two-story with basement. By 1949 when the building was in use by Southern Jobbers, two of the warehouses had been shortened and, with three new buildings, were used for storage of building materials. Four new dwellings had been built, all one-story. The tower still held the 3,500-gallon water tank. Summary of Significance This building housed the first cotton mill in Raleigh, a city better known for its political importance than for its industries. The Raleigh Cotton Mills building played a significant role in Raleigh's attempts, from the 1870s well into the twentieth century, to become a center of manufacturing and industry. It was built during the city's building boom of the 1880s and early 1890s. By the turn of the century, three large cotton factories and two large knitting mills had been established, and an author predicted, "the next ten years will witness a development that will double Raleigh's manufacturing plants. " In 1904, the Raleigh Cotton Mills consumed 1,750,000 pounds of cotton making hosiery yarn in its spinning factory. Nevertheless, the cotton venture was not a success, and in the late 1920s the mill was forced to close with the coming of economic depression. Despite earlier optimistic predictions, Raleigh remained less industrialized than most other North Carolina cities. Its retail business, rather than its industry, grew steadily and the city saw a great rise in trade and commercial investment. No longer needed for cotton production, the Cotton Mill's large spaces were adapted for warehousing in 1932, and Brown-Rogers-Dixon later operated its wholesale distributorship out of the building for forty-four years. The building served as a warehouse for significantly longer than its original use as a cotton mill. It was later (1995) adapted for a third use, as residential condominiums. |